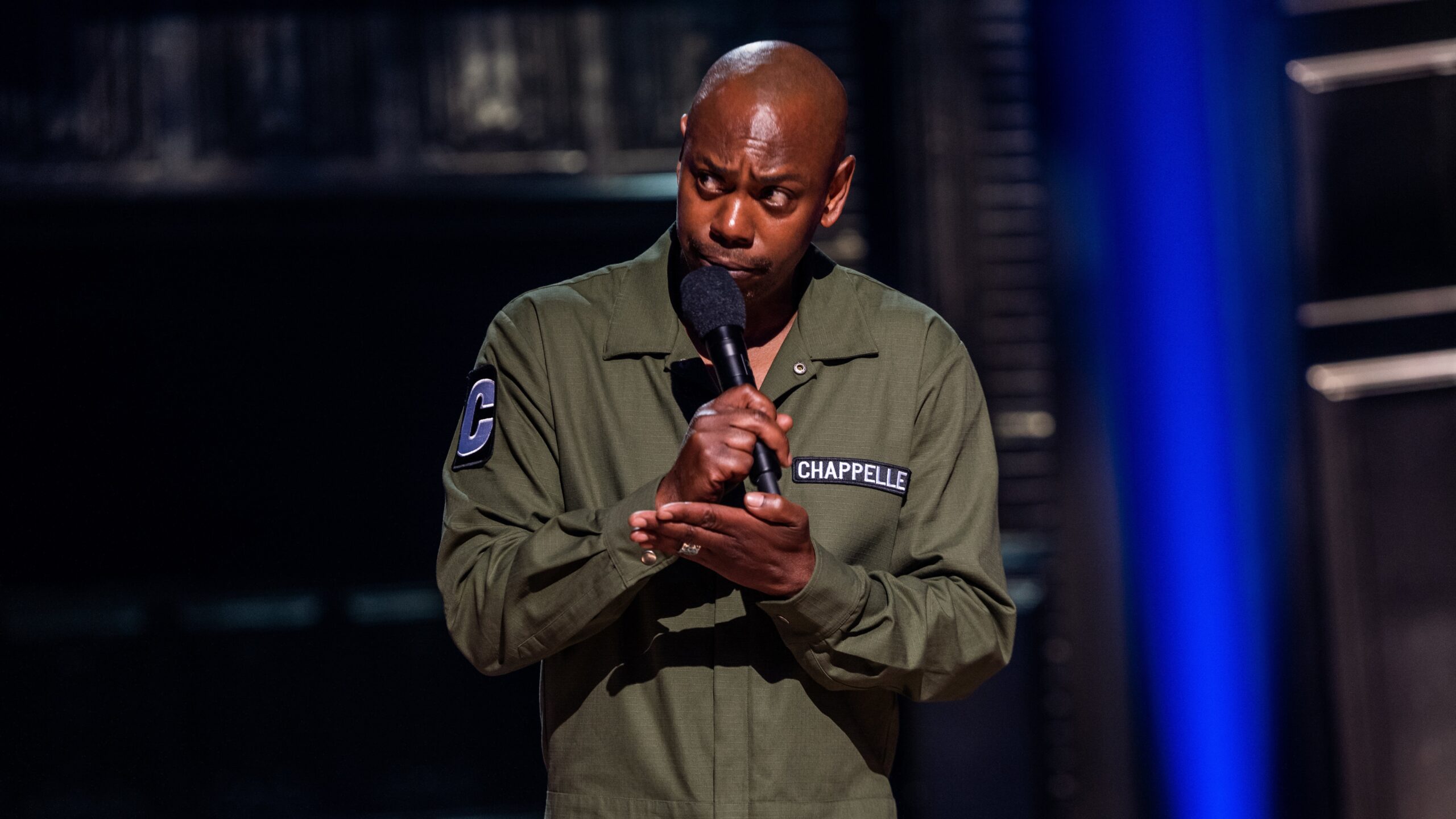

Dave Chappelle doesn’t really give a fuck what people think.

Wait, let me reword that—he does give enough of a fuck to respond to his critics with a one-hour comedy special, but after he says his piece, you can kiss his entire black ass. And that’s that on that.

Suggested Reading

In fact, he began his latest Netflix comedy special, Sticks & Stones with a Kendrick Lamar bar, “You mothafuckas can’t tell me nothin’, I’d rather die than to listen to you,” from the rapper’s hit single, “DNA.”

Allow me to start with the good: One thing I’ve always valued about Chappelle’s standup is his deft storytelling ability. He knows how to bring a story back full circle and keep his audience engaged enough to get to that ultimately satisfying denouement. He did just that in Sticks & Stones. His simple yet effective impersonation of America’s Founding Fathers was hilarious. Plus, “Juicy Smoulé” in place of Jussie Smollett’s actual name had me in tears.

And now? The critiques. I know he won’t care too much, but I still care. Baby!

The cognitive dissonance embodied by people who complain about “PC Culture” is astounding, as I’ve never met a whinier person than a privileged pillock who is challenged on their bigoted rhetoric. I swear hell will freeze over before the “freedom of speech” brigade realizes (or admits) that critique is another form of “freedom of speech” expression, not the dissolution of it.

In that same vein, I highly doubt standard art critiques automatically equate to “canceled” for a multimillionaire comedian. As Danielle Butler expressed in her 2018 VSB essay, “what people do when they invoke dog whistles like “cancel culture” and “culture wars” is illustrate their discomfort with the kinds of people who now have a voice and their audacity to direct it towards figures with more visibility and power.”

Much like students who graduated from the School of Speaking My Mind (my fave retort to this ideology is Tiffany “New York” Pollard’s, by the way), Chappelle’s latest special has been deemed “risky” and “edgy.” University of Texas, Austin, professor Robert L. Reece, Ph.D., addressed such claims in a series of tweets on Tuesday.

There isn’t anything truly risky about echoing the rhetoric routinely expressed by mainstream channels.

“Making fun of trans people is easy,” Reece tweeted. “Antagonizing people who call you homophobic is easy. It’s not cutting edge. It’s not creative. It doesn’t push political or comedic boundaries. It’s stale, and it’s lazy.”

While watching Sticks & Stones, my mouth remained a gaping hole, stating “Oh my God” over and over, particularly during the Michael Jackson segment. But, that’s it—just shock. Is that the ultimate reaction a comedian wants from their audience? Or is it, you know, laughs? And not the forced “uncomfortable laughter” that happens when someone says something outrageous and you don’t know what else to do. I mean, genuine belly laughs.

Smart comedy can be shocking, but shock value comedy isn’t inherently smart. So he said some things he wasn’t “supposed to” say. So what? Was there any added value to rehashing the same tired transphobic jokes other than sheer shock? Even his proposition to register all black people for guns to make a real mark on gun control wasn’t a wholly unique idea.

Chappelle once expressed how uncomfortable he was when he realized white folks were laughing just a bit too hard at his blackface skit, and concluded that perhaps his attempts at challenging stereotypes failed and were simply reinforcing them. How can that same self-awareness implode into an ignorance cloud when it comes to transphobia, homophobia and sexual assault?

Much like his “shocking” jokes, though, the realization that intersectionality matters since privileged people within an oppressed group will often parrot their oppressor’s language isn’t new.

This isn’t exactly an argument for “never punch down.” Some of the most lauded comedians have punched down on occasion, whether it was Richard Pryor or George Carlin.

As Mask Magazine puts it:

When we talk about “punching down” vs. “punching up” in comedy, we are talking about where the cultural power of a joke is weighted. The idea that humor should “afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted” has been a sort of moral directive for comedians for some time. Dorothy Parker argued that ridicule was best used as a shield rather than a weapon—in other words, as a defense mechanism for the victimized instead of a tool deployed by the powerful. George Carlin echoed this sentiment, observing that “comedy has traditionally picked on people in power.” Kathy Griffin, defending Michelle Wolf’s incendiary White House Correspondents’ Dinner routine, explained that comedians are supposed to be “anti-establishment,” and “disrupt the status quo.”

It’s not so much a matter of what is “allowed” in comedy, as it is about designating what constitutes brilliant comedy. Punching down is easy. It’s much easier to join in on a crowd of people kicking someone when they’re down. Oh, you made a fat joke? Join the (default) club of unrealistic beauty standards designed to strategically give people a body complex. Punching up is a disruption and it takes a bit more work to effectively land a joke than to truly humble a class of people who are used to constant praise and privileged status.

Chappelle taking extra time to defend himself by throwing the same unnecessary jabs at the “alphabet” (LGBTQ) community appeared to be the lazy workings of a bitter and annoyed comedian who realized he couldn’t lob his jokes into a laughing void. I’ve seen Chappelle be better than that; he’s better than that. Or… was.

Sticks & Stones may break his bones, but Chappelle likely has the best doctors in the business on call. Maybe that’s why he’s so complacent.

Straight From

Sign up for our free daily newsletter.