Tarana Burke will never stop centering Black women and girls in her work. Those of us who’ve followed the founder of ‘me too’ since before its global recognition know its initial iteration was as a vehicle to support Black and brown communities—particularly the women, girls and femmes who’ve so often proven most vulnerable to sexual violence.

Without question, November 2017 somewhat obscured that origin story, as, in the wake of the accusations against the since-convicted Harvey Weinstein, several white female celebrities unwittingly adopted the phrase Burke had launched as a platform years before. Despite a backlash from predominantly Black women who rose to restore Burke to her rightful place as the movement’s leader, the movement itself swiftly expanded in the process, largely compelled by a media narrative which forced it to accommodate (as Black women already so often do) the needs and voices of other survivors.

Suggested Reading

That didn’t mean Burke’s intentions were derailed—or in any way deferred. Having built one movement, she, along with other Black women leaders, recognized the need for another; one with a mission that was unambiguous.

“I hear this all the time—like, ‘Oh, ‘me too’ was co-opted by white women,’ or, ‘Oh, you know, you’ve been infiltrated by white women to some degree.’ That hasn’t been my real experience,’” she recently told The Glow Up. “My real experience has been that the mainstream media will not take their eyes off of white women—they just won’t, no matter how much we scream and yell [or how much white women ‘share the mic,’ so to speak]. So, as opposed to trying to undo something that’s been happening for a hundred years in media, let’s partner.”

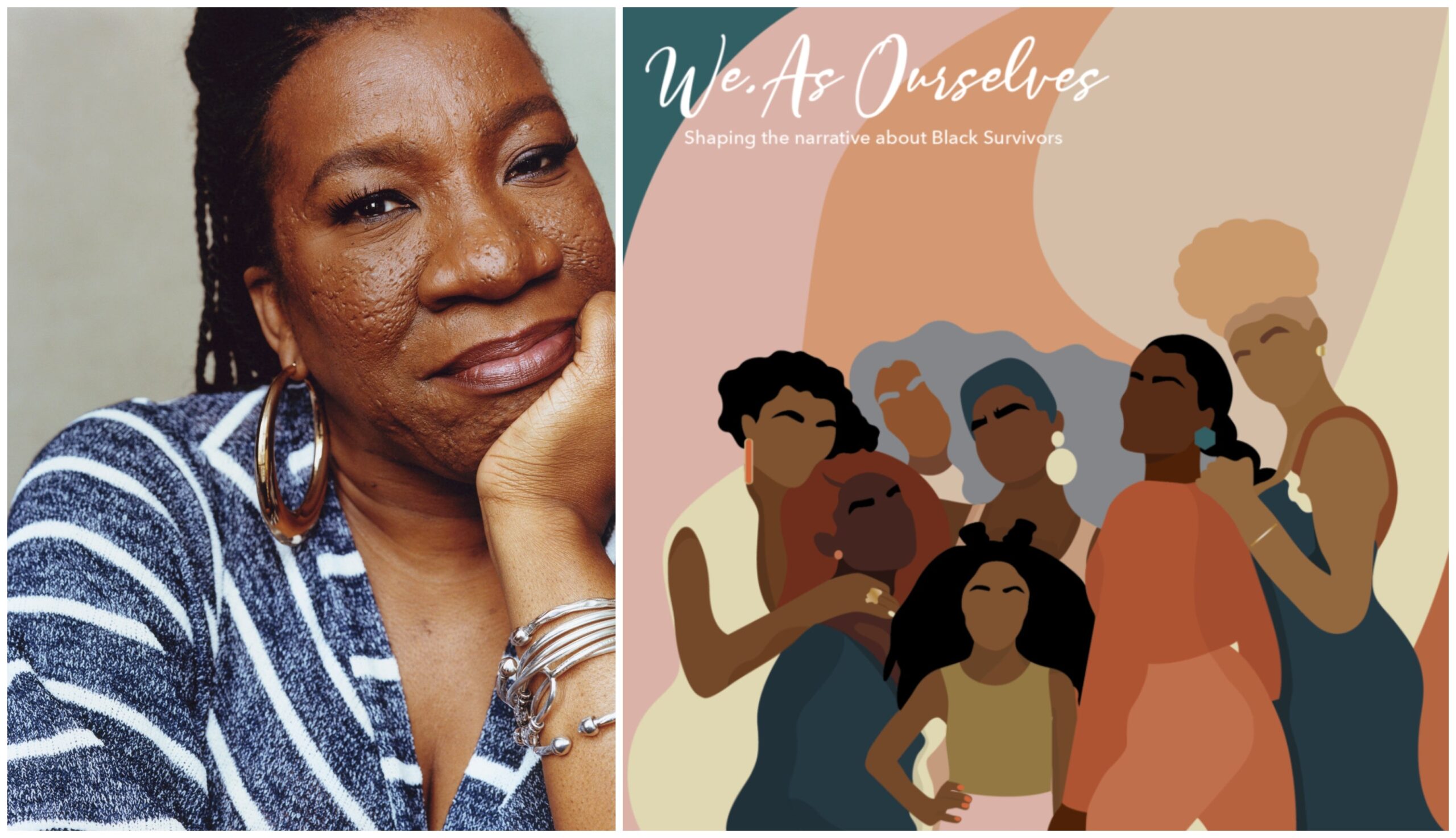

To create a conversation in which Black survivors could remain at the center, Burke partnered with two other Black women at the forefronts of national movements: Time’s Up Legal Defense Fund co-founder and President and CEO of the National Women’s Law Center Fatima Goss Graves, and former Senior Vice President of Moms Rising Monifa Bandele, now chief operating officer of Time’s Up. As reported by The Glow Up in February, together they launched We, As Ourselves, “a call-to-action to center the voices and experiences of Black survivors and to create the cultural conditions for Black survivors to be heard and supported.”

Reinforcing that urgency, this Monday saw the launch of the coalition’s first Black Survivors Week of Action, five days themed to drive a national conversation on how to support Black survivors. Tuesday’s theme? “Reimagine Survivorhood.”

“Black women, we’re always in this fight to be seen,” noted Burke. “And it’s this Catch-22 of like, hypervisibility—you know, ‘Black women save the democracy. Black women show up. Black women leadership this [and that]’...and it’s like a veneer,” she said, adding: “Y’all see us when you need to—like, ‘Oh, yes, yes, of course. Bring in the black women.’ And then, when Black women get there and we’re like, ‘Oh, while I’m here. I just kind of want to discuss this thing that’s hurting,’ they’re like, ‘Aht, aht, aht—we don’t really have time for that. Could you just keep your cape on while we’re talking? And we’ll get to the other stuff later.’”

It’s a conversation Burke and I have had many times before, both as journalist and subject and as friends (full disclosure: we were in each other’s orbits years before ‘me too’ hit the zeitgeist). Being well past formalities, we spoke frankly about the ways in which the mainstream media, politicians and even those closer to home have a tendency to cherry pick from Black women’s experiences, influence and expertise the parts that are useful to them, as if we are a buffet.

But this is perhaps most painful when it occurs intraracially, as does so much sexual violence—which is true of incidences of sexual violence and other offenses within every race. Yet it is most specifically and frequently Black women who are expected to atone for the ongoing vilification of both Black lives and Black male sexuality—often with our silence. Accordingly, I ask Burke what it might mean to reframe a conversation that repeatedly circles back around to what Black women owe the culture at large—the race at large—as opposed to asking: What does the race and the culture owe us?

“OK, let’s let’s let’s put it all out there,” answered Burke, who found herself a prominent commentator in both the allegations against Weinstein and against R.Kelly. “Let’s say that we don’t talk enough—hypothetically—we don’t talk enough about sexual violence against Black women that happens at the hands of white men. Let’s say that that’s the case, that we don’t ring the alarm enough [on white perpetrators]. What is it that you want the Black women who experience this intra-racially to do while you’re going around rounding up all these bad white men who are also assaulting, sexually assaulting, violating Black women?

“Should we just wait till you get to the whole list? Those things can’t happen simultaneously? We can’t both talk about what happens outside of our race and what happens inside of our race?” she asked. “Like it’s so blatant...it’s actually really sad. It’s just—it’s depressing...It’s is so corny but I just think about that Lauryn Hill (sings the famed lyric from Hill’s “X-Factor”)...‘Tell me, who I have to be...’

“Like, who do we have to be?,” she asked again. “We hold up the race. We hold down the culture. We show up when we’re supposed to; we stand down when we’re supposed to. What do we have to do? Who do we have to be to get a little bit of reciprocity? And so, yeah—this campaign is like, ‘We can’t wait.’”

Aside from the inherent gaslighting of any movement that expects Black women to be loyal advocates while not advocating for their own safety and survival, Burke also highlighted how counterproductive—and outright dangerous it is to focus our conversations about sexual violence on the few high-profile cases that make it into the mainstream discourse. “But we don’t really talk about what’s happening in the hood, right?” she challenged.

“We’re not really having that conversation—and so much of the conversation about Black women and sexual violence, in particular, has to be a conversation about child sexual abuse,” she continued. “It has to be a conversation about the adultification of Black girls. It has to be a broader conversation that is not about you and your homeboy on the corner. This is not about R. Kelly. It’s not about [also multiply accused music icon] Russell Simmons. It is really about that number that says that 60 percent of our girls will experience sexual violence before they’re 18.

“What happens to our trajectory when we get that number down?” she asked earnestly. “Because what you’re talking about is that 60 percent who are growing into these same women who are doing the voting and doing the saving and doing whatever with that on their backs. And then you’ve gotta add the next statistic that says that if that happens—if you experience sexual violence by the time you’re 18 and you’re a Black woman, then there’s a 66 percent chance that you’ll experience it again as an adult.

“We got to sit with those numbers,” she sighed. “If we don’t come to terms with this the real history of how sexual violence has become weaponized in the Black community, it makes the whole thing taboo. So you have decades of Black men who are falsely accused, decades of Black men who were characterized as hypersexual predators in the media—falsely. And we know that. And because we have Emmett Till or Central Park Five cases, it brings it up immediately, right? We have a sensitivity to that,” she acknowledged. “But part of it is because we’ve never interrogated how sexual violence was also weaponized against Black women. You can’t talk about the history of how it hurt Black men and not talk about Black women.”

On that note, much in the way ‘me too’ proved expansive, Burke concedes that We, As Ourselves, while “largely led by, talked about and framed as for Black women,” also presents an opportunity “to introduce a conversation about how sexual violence is pervasive in our community across the gender spectrum—people who don’t identify as women, people who identify as men, people identify as neither; it is absolutely pervasive.”

“At some point, we have to stop saying ‘what-about-whose-fault-blah-blah-blah’ and just take a step back and look at the thing and figure out what can we do about it,” she urged. “This really marks the beginning of a conversation.”

This is the first in a three-part conversation with the founders of We, As Ourselves. Learn more about their call-to-action and Black Survivors Week of Action on the campaign’s website.

Straight From

Sign up for our free daily newsletter.