One day, a white man walked into a clinic asking a doctor to check out a rash he found on his body. He described his other symptoms as a fever, chills, a cough and a sore throat. He was turned away because the doctor didn’t have a name for what he was suffering from. Then that man went home to his partner or maybe to a bar to go dancing and suddenly, more patients come in weeks later with the same symptoms. And they got turned away too.

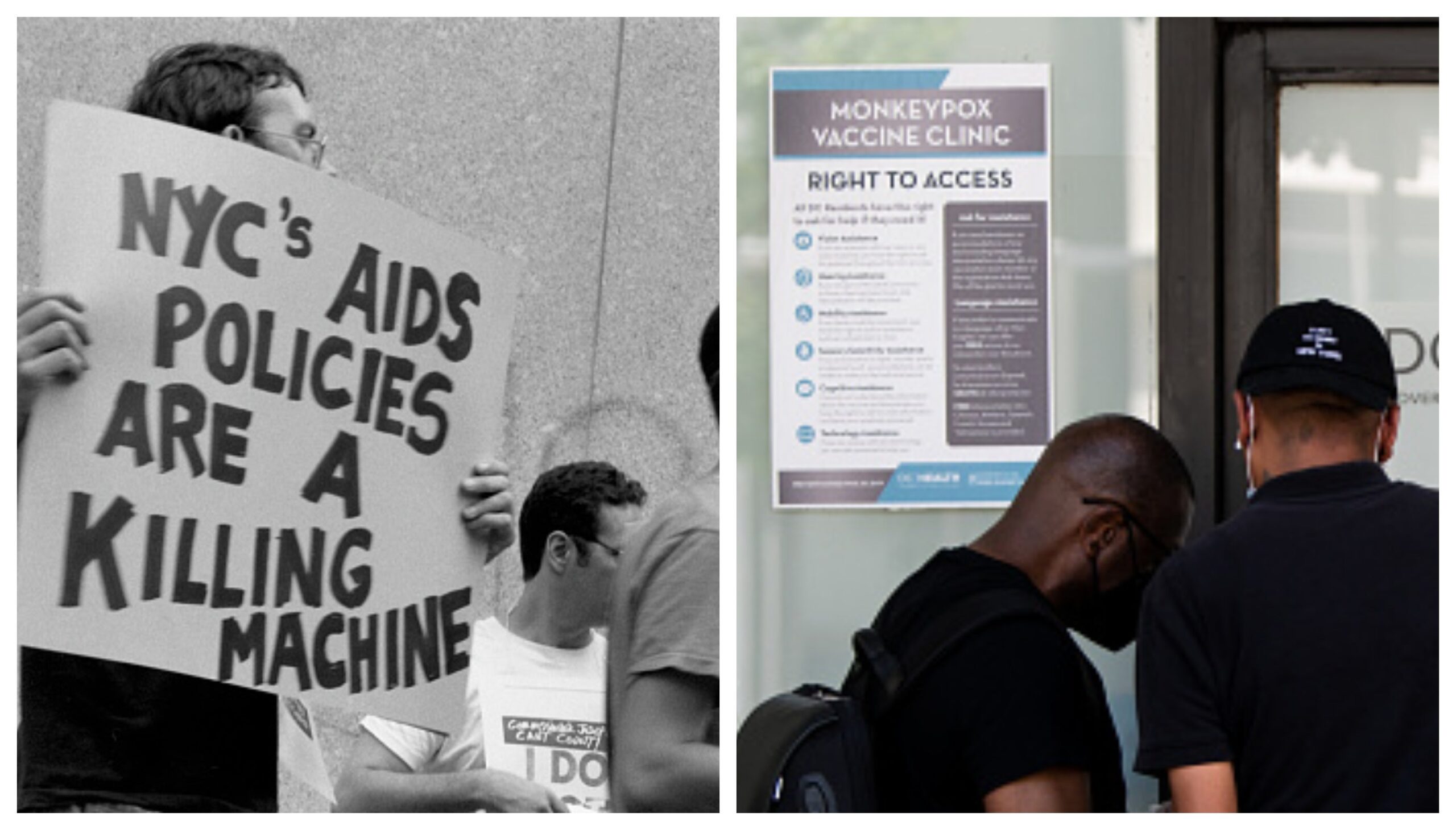

Later, the CDC matched those symptoms to an infectious virus identified as monkeypox (MPV). Ha. Now, doesn’t this story sound a little familiar? The HIV/AIDS epidemic began in an eerily similar way. Though these two viruses are not the same, society’s reaction to each of them was practically identical. TikTok doctors and big wig news outlets wasted no time labeling the virus as a “gay” problem.

Suggested Reading

A few LGBT organization leaders weighed in to discuss how we’ve time traveled back to the 80s with the new MPV outbreak.

“People living with HIV and AIDS went 10 plus years without hearing the President of the United States talk about HIV/AIDS, let alone create a plan to address it,” said Victoria Kirby York, deputy executive director of the National Black Justice Coalition. “As imperfect as the CDC may have been or continues to be on the MPV response, the fact that they are funding and are trying to get it right is vastly different – it’s worlds different from what we experienced in the 80s and early 90s with HIV/AIDS.”

The HIV/AIDS epidemic not only exploited LGBT people but also the Black people within the LGBT community. Torrian Baskerville, director of HIV and Health Equity at the Human Rights Campaign, recalled how HIV was considered the “white man’s disease” leading the response to it to leave out Black and brown folks. A similar disparity occurred with the distribution of COVID-19 resources and now we’re seeing the same with the MPV vaccine.

Baskerville said the majority of MPV vaccines have been distributed: in Chicago, 55% of vaccines have gone to white people, in Washington D.C., 63.5% of vaccines have gone to white people and in Atlanta, 54% of the vaccines have gone to white people. All of these cities have predominantly Black populations. Meanwhile, Black men make up the majority of the cases in states like Georgia and North Carolina, reports say.

“We can’t be surprised that these numbers are coming out the way that they are because again, the response is always going to inherently go toward [prioritizing] white individuals,” said Baskerville. “Sixty-seven percent of those first 452 cases were individuals living with HIV. We know already there’s a disparity within individuals living with HIV. Now you’re compounding MPV on top of that. – it’s important that we are intentional about ensuring that equity is ingrained and intertwined in every layer of this response.”

Even with all the new information we have about the virus, those initial “gay panic” reports left a nasty stain just like with the AIDS epidemic. Biased reporting led to the ostracizing of the LGBT community which cut them off from vital resources by isolating them into shame.

“We’ve seen that show before. We’ve seen how it ends with the HIV/AIDS epidemic where LGBTQ family members were kicked out because there wasn’t enough information about the virus. To be honest, service animals were probably treated better than the HIV/AIDS patients at that time,” said Kirby York.

“We know that stigma creates silence where people aren’t going to be asking for help or sharing things that they did over the weekend or other kinds of prompts that would allow someone to say who loves you to be clear to say, ‘You should go get that looked at,’ or ‘I know you like to party. I’ll go with you to get a vaccine.”

Straight From

Sign up for our free daily newsletter.